Notated Works

Traversing the Centuries

A recent excavation of Sumerian clay tablets inspired the text for this work. Anthony Goldhawk’s understanding is that the Sumerians were some of the first people to write hymns to music some 5000 years ago. Anthony has intentionally incorporated two themes in the text exploring his thoughts about these discoveries and what they might suggest about humanity. The first theme questions whether, over time, we forget the very people that created today’s world. The second incorporates the geological processes of weathering or the human processes of excavation, revealing what lies beneath the surface. Anthony describes both natural and human corrosive powers are capable of extremes of beauty and destruction. The text ends on a hopeful note, that even if we forget our ancestry, blanket the truth, corrupt beauty, and hide the past, it will always rise to the surface eventually.

In this work I attempted to explore the different viewpoints from which this poem could be read. The text discusses a view of historic construction from descendants’ point of reference, perhaps suggesting a present existing in a ‘now’ time. However, the text also firmly acknowledges that a present ‘now’ existed in the past for our ancestors, though it lies obscured from the direct view of their descendants, us. The text suggests that although this history may lie obscured that it still exerts a direct influence on our lives whether we understand or accept this influence.

I intended to blend the discovery of the ancestral histories and the present world together throughout the work, in essence gradating between the narrative of the present and the narrative of the past. As the text was visually presented in four couplets separated by a paragraph these appeared as sedimentary layers, evoking the themes of excavation and erosion. Therefore I chose to build a work where the musical framework repeated four times. The piece therefore has a varied strophic form and becomes more complex as we move towards the close. Each time this framework was to be repeated more and more music would be discovered ‘between’ the notes that existed in the previous section. Therefore, the work becomes more complex during the course of the piece and highlights the viewpoint (or narrative) from the present perspective at the opening (with notes obscured from audibility), and the viewpoint from the past perspective at the close (with all of the notes fully excavated). In other words, the detail of the piece is therefore excavated or eroded to the surface much like the poem suggests. A musical motif I intended to bring out was an accelerating crescendo which in this piece trills, mostly, on the interval of a third and is cross threaded and layered in the piano lines, also occasionally in the vocal line, throughout the piece. Further to adding more pitches and augmenting gestures in the musical lines, another technique was used in the vocal line where I augmented the syllables into sub-syllabic components. For example the single syllabled word ‘flesh’ becomes a two-syllabled word ‘fle-sh’ in the music.

I found great reward in writing the vocal line for Traversing the Centuries. Exploring the pure aspects, or rather constituents, of a single word brought about a discovery of more ways in which I could stretch and pressure particular sounds to enhance the narrative of the text. For example, the final word in the vocal part suggests a ghostly whisper from the ancestors spoken directly through the final sub-syllable of the narratively present singer.

Notated Score :- Traversing the Centuries

Abiogenesis

Abiogenesis – the evolution of living organisms from inorganic or inanimate substances. This piece is designed to illustrate a murky primordial soup that develops towards a living rhythmic entity by the close. One of the key features of the work is a breath-like crescendo gesture appearing throughout the piece in various guises (bb.1-2 /bb.11-12/bb.59-62). This doubles as a churning near the beginning when played by the whole orchestra (bb.17-20). This breath-like gesture builds to many anti-climaxes before the main climax of the work begins (b.97). The main dense section of the work preceding this climax (bb.68-96) is representative of the creature taking its first breath and the potential that this breath means for its life – now it is living. Following this portion is the final section of the piece where we can hear the creatures living heartbeat played across the orchestra; the creature’s excitement at its first breaths now subsiding with its diminishing heartbeat.

While using fairly standard orchestral instruments I attempted to create “primordiality” by using pitch-class sets incorporating quartertones, which are intended to be played consistently. Further to this the orchestra is exploited gesturally and, largely, as one sounding body in the opening. Contrasting this homogenous use of the orchestra it is split into families during the section preceding the climax (bb.68-96) with a premonition of this occurring in the double-horn solo (bb.40-54) where the double-horn emerges out of the texture for the first time. Double-horn is a descriptive term for the conception of an imaginary instrument. While prescriptively a closely connected heterophony is heard between the Horn duo, their lines are conceived as contributing to a single instrument that struggles to break out of its own musical line; we may imagine this as analogous to a butterfly struggling to emerge from its chrysalis, the two horns being the single butterfly and the chrysalis being a single musical line sitting somewhere between the average of what is notated between bb.40-54.

The chance to work with orchestral forces for Abiogenesis allowed me to experiment with a new method of composing. Prior to this work I’d spent a lot of my time composing at the piano to discover the pitches and harmonies I wished to use in my works. While I enjoyed the audible feedback given by the piano, for me, this came with the drawback of creating moments of inconsistencies on the page that did not match the ‘score’ in my head. My explanation for this is that in my exploration of many different versions of a particular musical moment, while composing at the piano, my psychological reaction to eventually having to choose only one of these moments was ultimately unsatisfying and thus lead to the disparity of the real single-score with my imagined multi-score. I would call these moments ‘fluxing’ as they never seemed to have completely phased into the score of the real. While an odd psychological phenomenon I’m still aware of it when composing at the piano to this day. For Abiogenesis I intended to completely remove the piano from my method and instead focus on just the creation of the real score.

As I was no longer bound to the piano to gain my harmonic language I instead used the technique of selecting pitch-class sets for various sections and subsections of the work. I found I naturally aimed towards this harmonic technique to consolidate harmonic consistency across small-scale events within the work.

At the time of writing this work I had been experimenting with creating generative harmonic consistency within a computer program. I had designed a small program that would randomly generate notes in a single musical line one after another at constrained random time intervals. Combining two or more of these generating musical lines created harmonic interest. The question that arose was how to create a harmonic consistency between two or more randomly generating musical lines. The full discussion can be found in chapter 2 of the accompanying critical writing; however, my conclusion was to provide the computer with specific predesigned pitch-class sets which force the generative engine’s decisions to be that of only concurrently pleasing options. The idea of a stable pitch-class set evolves into the concept of a harmonic-cloud in my critical writing—a stable area of predictable harmony in a generative musical environment, allowing the predictability to be used by the composer to affect.

Notated Score :- Abiogenesis: First Form

Interactive and Generative Works

The three following works are designed as three parts within one meta-work which can be accessed by downloading and running the InteractivePortfolio_Application. Tutorials for which can be found here.

The choice to make the interactive portion of this portfolio a single meta-work was one born from my love of video games. I wanted to create a meta-work that could explore some of the concerns I have about dynamic music in video games and also create an overarching personality to some of the more automatic works included in my whole portfolio (including the notated works). The overarching theme–one which I have always been fond of–is that of the combination of humans and technology or nature and humanity. Being the creators of technology and, at the same time, a creation of nature (in only my personal belief), humanity is impossible to separate from these distinctions and the exact place humanity sits with respect to either is uncertain. This makes the contrast, or juxtaposition, between humanity, and its interaction with either (nature or technology) an extremely interesting concept for me. These concepts are found in every work of this portfolio.

In considering the interactive portfolio itself a work, I would draw focus to the fictional ship’s artificial mind liaison (PAMiLa). The synthesized voice of PAMiLa guides you through the portfolio, in the tutorial; generates music for you, in the generative triptych of percussive music; creates a narrative and accompanies it with music, in Deus Est Machina; and ultimately decides your fate, or at the very least your entertainment, throughout all of these works.

However, PAMiLa is not without its human flaws. As the listener will gather from the opening sentences of the tutorial, PAMiLa has an irksome relationship with ‘bios’ which leads it to try to wrest control of the ships flight systems during Starfields (FLIGHT MODE) and decides your character’s fate throughout Deus Est Machina (NARRATIVE MODE). The listener will also quickly notice PAMiLa’s god complex when describing its ‘own’ works as “gifted” and suggesting the creation of sonatas as a trivial task. The listener will also notice that the writing style is very factual and sometimes cold, suggesting that PAMiLa’s own view of its writing is not necessarily correct and perhaps doesn’t display the human warmth we may expect from a human writer. I am suggesting that even an Artificial Intelligence can display something that we often attribute only to humanity.

If your system will not run the InteractivePortfolio_Application then musical recordings, multiple generations and excerpts have been provided in their respective sections.

Generative Triptych of Percussive Music (MUSIC SYSTEMS): in InteractivePortfolio_Application

In this note I will explain the code for the generative triptych. I will then go on to explain some of the interesting explorations within the individual works contained within the triptych. Towards the end of the video is an explanation of how you can compose your own scores for this instrument within the Interactive Portfolio. Help on ‘How to Operate’ can be found at any time within the portfolio by clicking the help interface in the bottom right corner of the interface.

The individual works within this triptych are explorations of an instrument of my design. The programming language ChucK, designed for Princeton Laptop Orchestra was used to code these works. Herein I include the design of the instrument.

This instrument was designed to generate individual bars of music. I first designed a class, which I named generateBar. This class included a play method. Upon calling this method the bar will be generated and played. The play method accepts various different parameters, which define the qualities of the bar to be generated. Although the created bar’s microcosm is at the computers discretion the macrocosm is determined within the specified parameters. Within these parameters are: the chances for a specific sound file to fire, the number of beats in a bar, the bar’s tempo and number of repetitions of that bar. The method of generation is similar in each of the individual works.

The parameters controlling bar beats, tempo and repetitions are self-explanatory. Beats are accepted as an integer greater than 0; tempo is accepted as an integer in BPM; repetitions is accepted as an integer greater than 0. Those determining chance require a small amount of extra explanation.

Chance that a specific sound will be played is determined through the following algorithm: A number is set for the total number of beats in the bar, in our example we will use the number 8. Then a number is set for how many chances a specific sound will play, lets take the number 4. As there are 8 available beat slots to fill the program will now determine randomly 4 times which of these available beats the sound file will play on. If we take the generations to have produced a 1, a 5, a 8 and another 1. Shown here is that each individual roll was unrelated to the last and therefore two 1’s were rolled. The bar produced will play the sound on beat 1, beat 5, and beat 8. As there was a second 1 rolled and beat one had already been filled, this second roll is disregarded.

Careful choice of the ratios between these two parameters results in many unique outcomes. Two examples employed in this portfolio are discussed below. In a bar of length X, giving the sound file only a single chance to play will produce a certainty that that sound will play exactly once during that bar. Conversely, in a bar of length X, raising the chances above the value of X can produce greater and greater chances that the bar will be filled completely. The opening bars of the generative sonata for synthesized drum-kit use both of these techniques simultaneously. I describe these techniques as the standard techniques for this instrument.

The structure of these works is created by many consecutive calls to the play method. A video programme note to this work is provided on the accompanying DVD and should be viewed in parallel with this text programme note.

Two more advance techniques became apparent to me upon composing the second and third works in the triptych. The first is regarding the composite-bar. A composite-bar is a single bar made up of many different calls to the play method. These contributing calls are each made up of highly likely parameter combinations. The effect of this is the ability to create defined gestures in a work of highly chance-like material. This technique is used in the second work and more prominently in the third.

The second advanced technique was in the types of sound files chosen. In the third work, the use of vocal sound files allows a greater freedom of expression through use of the tempo parameter. This is due to the rich qualities found from within even relatively small duration vocal sound clips. Longer or shorter tempos combined with the instrument’s percussive repetition allowed these micro-qualities to come to the fore in the third work. In the first two works I had kept my choices of tempo change to mathematical ratios of the tempos immediately preceding or succeeding. I had also generally maintained patterns within sections.

I believe this work is successful in creating variety over multiple playsthroughs while maintaining the essence making each composed work its own. Therefore multiple playthroughs become a feature of the work. It’s important to note that it was not the intent, from my point of view with this work or any others in this portfolio, to create works of infinite interest. The term ‘multiple playthroughs’ here refers to an equivalent interest that might be achieved from multiple recordings of an acoustic work – greater than zero and yet non-infinite. In other words, though the number of variations a single score of these sonatas could produce is very large I do not see a listener’s interest extending to this number of iterations. This is a psychological feature bound by humans’ innate skill at pattern recognition. More research would be required to find a point at which these works no longer excite due to this biological feature.

The video programme note/demonstration goes on to demonstrate how to use the ‘Compose your own’ scoring system within the Interactive Portfolio application and should be viewed by the reader now.

Full ChucK Code for all Works :- Generative Triptych of Percussive Music

Starfields (FLIGHT SYSTEMS): in InteractivePortfolio_Application

Starfields began as a musical project designed to fill the often large temporal space between individual pieces within a concert of The Oxford Laptop Orchestra of which I was a directing member in 2012-2013. The original version had a single section of reactive intensity. Within this section the user was able to adjust the degree of intensity of the texture by sliding up and down a software fader interface (in MaxMSP is known as a slider). This was useful for creating music of a dynamic length to fit in between points where unexpected technical issues occurred in the set-up of new pieces. It also had the added bonus of enabling a musically sensitive operator to react to their perceived ‘needs of the moment’ and increase or decrease the textural complexity of the music.

This version of Starfields (Starfields 2.0) is a fifteen to twenty-minute work incorporating this same design in its opening sections. The piece also goes on to explore many alternative ways in which musical intensity can be changed with this same control mechanism and eventually explores the notion of player-control itself.

The role of MaxMSP within this work is twofold. First, MaxMSP has been used to provide an appropriately simple user interface that can be run on any reasonably powerful OSX machine. Second, MaxMSP runs all of the under-the-hood processes involved in the transference of user action to audio. This involves selecting sound files, choosing whether or not to play them, running any random chance decisions, running the artificial intelligence, moving through sections, timing sub sections, filtering audio, and even performing as an electronic oscillator soloist in the later stages of the work. All sound files (900+) were composed outside of MaxMSP. To this end, MaxMSP is a tool for maintaining and enforcing the structural architecture of the work while providing the user interface and user control.

The piece comprises twelve discreet sections, which explore the interplay between these different levels and modes of control. The majority of control in this work is done by a single slider controlled by the user on the right of the screen. The slider enables the user to move vertically through the piece. There is also a behind-the-scenes counter that moves the piece horizontally through the sections. The counter counts in seconds and, at certain trigger points, engages a transition to a new section or a modified version of a section already heard. The majority of these sections were composed to last for an indefinite amount of time. However some have defined ranges of time-space. Compositionally this amounts to the more defined sections having more time-sensitive triggers.

Each section’s linear movement is built around a looping subcounter which is detached from the main counter propelling section changes. This subcounter will count sixteen beats and then recount them ad infinitum. Most sound files are initiated on one or more of these beats with each sound file being given its own initiation parameters. On top of these initiation parameters are chance-to-hit parameters that give certain sound files degrees of likelihood above zero to be played. Therefore the average file will have two parameters. First, the beats it can possibly initiate on and second, the chance that on these beats it will initiate. For example: snd_01.wav; can activate on: beat 1, beat 5, beat 9, and beat 13; with a chance of 75%.

Some sound files are governed separately to this and trigger at specific points after the start of the section. These points are either defined exactly or given a range of potential starting points after the triggering of a new section.

In the most recent version of the work I have added in three minigames. The term mini game comes from the gaming community to mean a game within a game. These are often easy-to-solve tasks taking place within the narrative fiction of the game, or in this case, the work Starfields. The three minigames add to the ‘control’ and ‘interaction’ texture of this work by allowing the user to have ostensible control over the narrative of the work. The control mechanisms of the mini games and the narrative context of their temporal positions in this work are explained towards the end of this video. Help documentation can also be found within the main interactive portfolio.

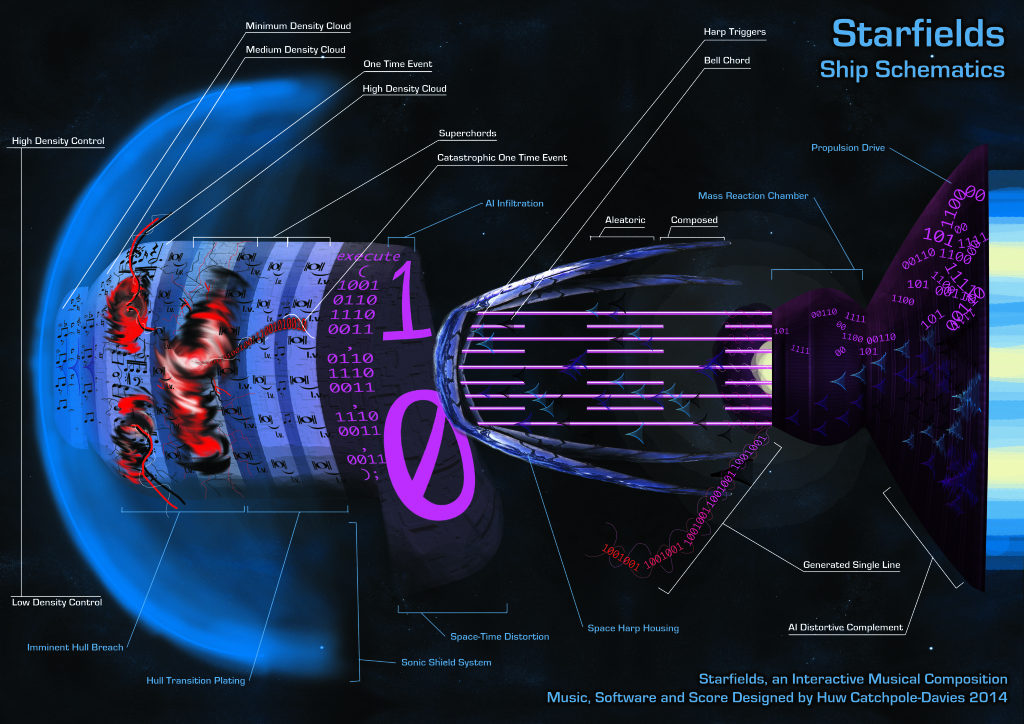

Notes on the Graphical Score

The score for this work can be read as any other score, from left to right.

Your slider position represents a location upwards or downwards on the hull and so a path could be traced for any single hearing of Starfields.

There are two competing musics juxtaposed within the work. That of the human, scored in western notation and are sonically made from more complex acoustic sounds; and that of the computer, scored with 1s and 0s and are sonically produced from much simpler mathematical synthesis.

The piece also incorporates one-time events which trigger once only during the work. One-time events are composed analogously to a linear work and provide moments of definability amidst the chance-like subtleties making up much of the rest of the work.

The piece comprises twelve discreet sections, which explore the interplay between these different levels and modes of control.

More details on the Sections

Section 1, 2, 3 and 11

Section 1, 2, 3 and 11 comprise independently layered musical textures, which the user can move through with the slider. Each sound file acts as a stem of the full texture. Moving the slider above or below certain thresholds activates or deactivates the stem from the texture. Each stem is made up of a pool of similar sound files, which are randomly selected by the computer. The three sections are contrasting in overall density and occupy different harmonic-clouds (a concept discussed in Chapter Two of the accompanying critical writing).

Section 3 also incorporates a one-time event which has different parameters based on both the location of the slider at the trigger point and an element of chance (this is known as salt in cryptographic computing). Some permutations of this section are shown in the excerpts folder within the portfolio file.

Section 4 and 6

Section 4 and 6’s music are no longer stems of individual instruments but stems of a single superchord with many partials. Each partial is given its own stem and the user can sweep up and down to explore the timbre. The control reacts much quicker to the user’s inputs than the previous three sections. Section 4 is the first section to directly disable the user’s control of the slider thus introducing the AI character (PAMiLa, discussed above) to the narrative. These superchords are labeled on the graphical score provided. At brief moments the artificial intelligence controls the slider. The AI displays a number of different personalities which manifest in different slider movement styles. Some of the personalities include: slow movement, quick movement, large ranges, small ranges, specific ranges, non-specific ranges, etc. Coupled with the interjections of the artificial intelligence are new textures of sound that represent the artificial intelligences sound world. These sounds are overtly electronic in nature often incorporating much distortion, noise or regular mathematical fragmentation of the sound wave.

Section 5

This section is entirely composed with a single one-time event which expands on the material introduced in section 4. At this time the user has no control over any of the sound. While movement of the slider is possible, no sonic effect is made. Further, the AI takes control of the slider for much of the portion of this section. This is intended to make the user feel like they are battling over the control of the slider.

Section 7 and 8

The music of the AI has taken over during this section. However, the user has complete control over the density. Density is achieved in a different way from the previous stem activation method. In this section there are many primed play objects ready to send a file to the DAC. Increasing the sliders value will cause more of the primed play objects to fire. The sound files used in this section are quite short and their erratic nature blends well with the erratic control method this section allows.

In Section 8, the user has control over the same files that played in section 7 but no longer is there many different primed play objects. Now there are just two looping play objects which continually fire immediately after they have finished the previous files. One of these play objects is playing electronic files from the previous section and the other is playing harsh yet regular drum patterns. The user has control over what speed these files are played back. Therefore difference in texture is here controlled by slower or faster rate of sound file playback that I intended to produce the illusion of density changes.

These sections are the first example of temporal transformation of the sound through time as opposed to looping.

Towards the end of these sections the spaceharp is introduced. The spaceharp is a digital instrument of my own design for this interface. The spaceharps pitches trigger from the crossing of thresholds in both directions giving it an analogous impetus to the acoustic harp. The sound of the spaceharp is a modified pluck sound source giving it further analogy to the acoustic harp. Added to the decay and sustain portion of the waveform is a bending generator which will bend the pitch of the note up or down over a specific range. This bending generator is pushed to its most notable limits in the second hearings of both section 9 and section 10. In this section the spaceharp is played behind-the-scenes by the AI and uses the hybrid melodic generation process that is discussed in Chapter Two of the critical writing accompanying this portfolio.

Section 9 and Section 10

Section 9 and section 10 are best considered complementing counterparts. Each use the same timbres (the bellchords and spaceharp) but have vastly different compositional structure. Section 9 is governed by chance and Section 10 is hard composed. These sections are repeated afterwards with a generated melodic accompaniment from the AI which attempts to find its footing, through complementary music, and does so towards the end of the section.

Section 12

Section 12 is the finale of the piece and conceptually returns the intensity control back to the domain of time. Though the operator is completely human throughout this section they are in control of very little of what makes the final minutes of the work complete. The entire section takes the form of a giant swell. Much like the user has been able to increase intensity by moving the slider up the screen the intensity is now temporarily achieved.

Throughout this section, material from the one-time events in section 3 are revisited and given new timbres, related to the mathematical timbres of the previous section. The computer now selects larger fragments of precomposed melody and has control over the order in which they are played. Much like the bellchords of section 8-10 the computer is given the opportunity to play multiple lines of these fragments simultaneously. As these are chosen at random and delayed by a random number of beats this allows the opportunity for many different combinations and interplays.

During the evolution of this section there are background swelling chords that are also derived from earlier swelling material such as the bellchords of section 8-10 or the transitional swells between the opening sections 1-3. These swelling motifs move more and more into the foreground and become more and more computationally corrupted. However, here this corruption is complementary to the texture. This completes the combination of the juxtaposing materials representing both human and AI.

New Additions to this Version of Starfields

Interface

The score for this work is accessible within the main interface by selecting the NAVIGATION DISPLAY. When the engines are engaged a small sprite represents the players location through the work. Further to this, on mouse-over the descriptive labels for the score can provide further detail on any labeled score element. The descriptions for these labels are written from a perspective outside of the fiction of the portfolio to aid the player more readily.

MiniGame 1

During the first MiniGame the AI is attempting to take control of the audio system and is in the process of transferring access of this system to itself. The MiniGame takes the form of a ‘button battle’ with the AI where the player must press SPACEBAR faster than the AI can. When the player presses SPACEBAR the cursor in the centre of the screen moves towards the left. When the AI presses its virtual SPACEBAR the cursor in the centre of the screen moves towards the right. The music for this MiniGame actively adjusts levels of stems of two competing musical minicompositions. These compositions both complement each other, for example, in terms of texture, rhythm and harmony; and contrast each other, in terms of timbre and intensity for example. The two musics of this section also sit within the superchord texture being produced by the section (Section 6) this MiniGame inhabits.

MiniGame 2

During the second MiniGame the starship is adrift without functioning engines; the player here is attempting to reboot and calibrate the engines in order to continue the onward journey. The MiniGame takes the form of a ‘call and response’. The computer generates combination of pitches connected to a coloured button and the player must repeat this pattern back accurately. 5 stages must be completed without mistake. The game starts with a 3-part combination stage and ends with a 7-part combination stage. Should the player not be able to pass this MiniGame successfully in the allotted time then the game switches to an easy-mode. In easy-mode the game switches to a 2-part combination with only a single stage to completion. The musical sound effects within this section complement the surrounding texture.

MiniGame 3

During the third MiniGame the starship has triggered a synergic Co-Pilot testing procedure as it has identified the player and the AI as cooperating pilots of the audio and propulsion systems. This is intended to reinforce the idea that the once corrupted AI is now working with the player in its output of musical material. This is the cue that the final section of the work will be wrought through the jolly cooperation of both computer and human materials. The MiniGame takes the form of a ‘hitbox reation’ test. The black bar swings back and forth and the player must hit SPACEBAR when the black line falls within the green area. The AI pilot also performs a similar task on the right hand side of the screen. 6 stages must be completed before the final section of the work will play.

Click the Image for a version in Full Resolution

Deus Est Machina (NARRATIVE SYSTEMS): in InteractivePortfolio_Application

This work was designed to exploit the GMGEn (Game Music Generation Engine) instrument that is described during Chapter Two of the critical writing submission accompanying this portfolio of musical works.

The instrument is designed to accompany scenes with short-term (less than two minutes) musical personalities (described in Chapter Two of the critical writing submission) which are generated on-the-fly by the program. The instrument can also dynamically transition between these musical personalities through path-finding mechanics I designed into the program. These mechanics traverse the musical space between styles to create an unbroken through-composed generative work of automatic music. Described further in Chapter Two of the critical writing submission are the processes involved in the creation of the underlying engine as well as some of the artistic constraints and freedoms I have imposed on the instrument. Important in this discussion is the chance for unsuccessful transitions and the artistic choice behind not creating an engine capable of purely “successful” transitions (this discussion can be found final paragraphs of Chapter Two of the accompanying critical writing submission).

On top of this instrument is a narrative of my own creation. The narrative is designed to have a non-linear structure and to take the player to specific locations. Due to the non-linear structure, many concerns had to be taken when writing a non-linear narrative that inevitably must be heard linearly. I found a solution to this chiefly in creating a predominance of descriptive passages rather than expositional portions in the writing. These descriptive passages directly exploit the state-based nature of the accompanying GMGEn instrument. While greater narrative exposition would have required generating music capable of directly following the, what here would be temporally indeterminate action, conversely creating largely descriptive passages of text supported the descriptive scene-painting output of GMGEn.

The visual design concept for this work is reminiscent of JRPG’s of the late 80s and early 90s, which I played in my youth. The player is shown scrolling passages of text, which they read to garner information about the imagined world of the narrative, while accompanied by music generated by GMGEn. In this format the player has the choice to move on through the text at their leisure, by clicking CONTINUE buttons. In other words, this text can now be read, or reread, by the user at any speed. This creates a atmosphere and temporal space in which the musical generation of GMGEn can thrive.

While this work fully utilises GMGEn’s functionality in generating static material and triggered transitional material, I also believe it’s successful at invoking the god in the Machine, which can be read on several levels. In a self-referential way PAMiLa is the titular machine of the story while also being that story’s fictional creator, its ‘god’. This functions within itself (the piece: Deus Est Machina) and without by reinforcing the meta-narrative of PAMiLa as flawed storyteller to the onboard pilot (you, the listener). You may interact with the work in some scenes allowing you to decide your choice of exploration; however, it is the AI (PAMiLa) who will decide your ultimate fate throughout the story. Some sections of the narrative form a mobile structure and some are branches of potential options, which are decided by the listener. A detailed version of the sections and their structure are provided in the score with a full narrative script (of all possible options) also included.

Score and Full Script :- DeusEstMachina